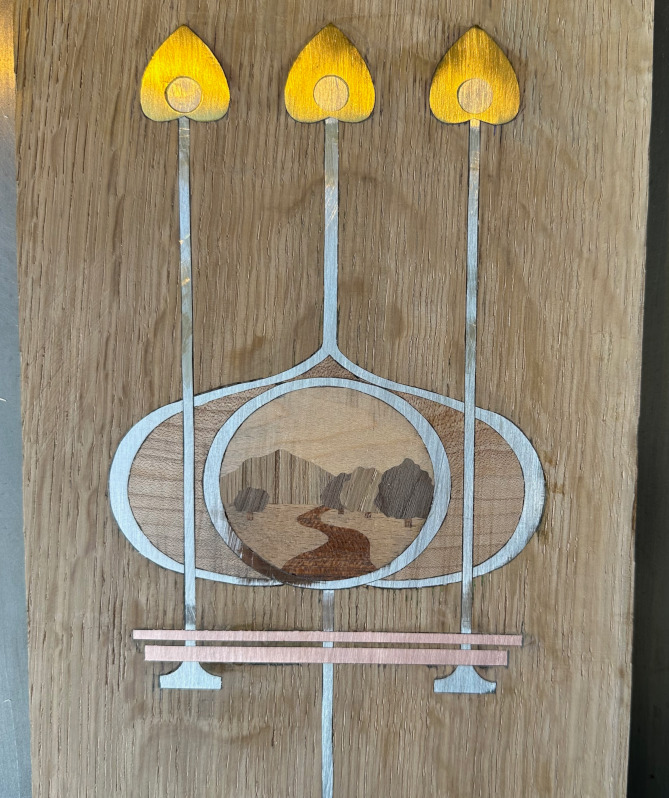

How’s that for a click bait title? But I really did spend almost a year on this with most of that time eaten up teaching myself how to do marquetry and inlay work. As I mentioned before, my first attempts didn’t go well and I spent a lot of time searching for advice on how to do this particular style of Art Nouveau work that almost nobody does anymore.

Sanding and finishing metal and wood right next to each other also proved difficult and I’m not entirely satisfied with the result, though even I couldn’t see the imperfections once I put the bed in the bedroom. The bed is made of solid, quarter sawn white oak and it’s HEAVY.

The inlay includes, maple, mahogany, cherry, birch, oak and walnut all sourced from scraps from other projects and cut by hand with a jeweler’s fretsaw using the double bevel method. The metal is copper, brass and pewter. The straight lines were made with plumber’s solder that I hammered into place and sanded flat. I modified the original inlay design by adding a tall mountain to make the scene more California. Almost all the supplies and tools for the metal work came from LA’s massive downtown jewelry district, a resource that proved inexpensive and convenient.

The oak I was working with was from the bottom of the pile and not the best quality. It’s also hard to find thick white oak here in California so I had to glue up thinner pieces to make the big horizontal stiles. The tapered legs are also built up from smaller pieces and veneered on two sides so that the medulary ray pattern appears on all sides. This is a detail only nerds will notice. I finished this beast with the sort of dark stain that has fallen way out of favor these days and I felt counter-cultural applying it.

The design of the bed is, allegedly, by the architect and artist Harvey Ellis who worked for Gustav Stickley and it’s, apparently, a prototype that was never put into production. The Stickley company still makes a version of this bed. The design looks a lot like the two settles that my friend Jimmy and I built that were designed by the architect Henry W. Wilkerson so I wonder if the attribution is accurate or if Ellis just designed the inlay work.

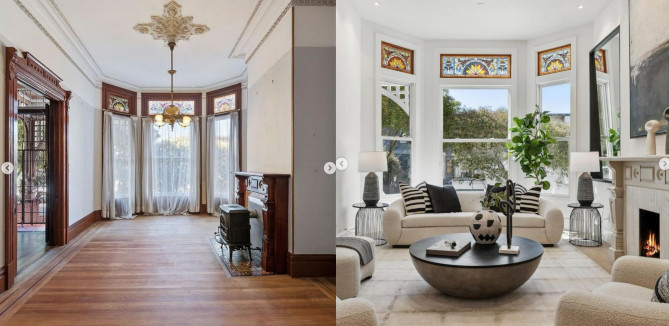

I like the dreamy, magical, vaguely medieval quality of the furniture and architecture of the years between 1900 and 1915 before the horrors of the 20th kicked in. My near term plans involve laying in this bed imagining the fin de siècle odors of absinthe and incense as I drift asleep reading Arthur Machen.

The print above the bed is “Floating Up” by David Huggins which I learned about via the amazing documentary Love & Saucers.