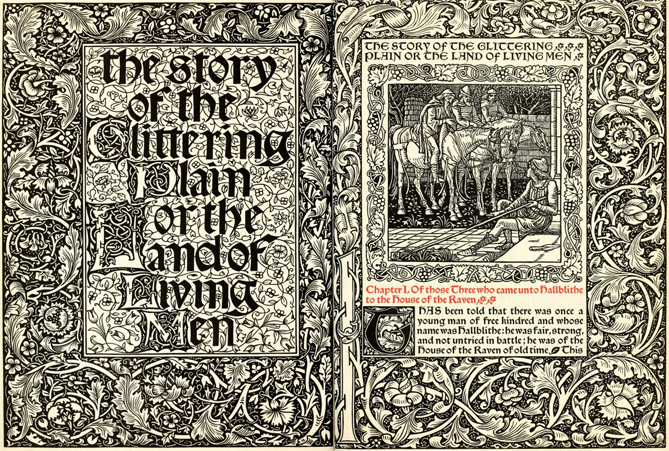

I’ll cop to being a Marie Kondo fanboy in the wake of the de-cluttering trend of the early 2010s. And, no doubt, I’m thankful to have weathered lockdown in a mostly clutter-free house thanks to Kondo’s prompting. But those days in quarantine exposed some serious shortcomings in Kondo’s thinking and elevated in my mind her more thoughtful predecessor, the Victorian poet, designer and artist William Morris. An address Morris delivered in 1884, entitled Art and Socialism has a hint of Kondo’s decluttering impulse but a much deeper and less individualized understanding of the meanings of the objects that clutter our lives.

Kondo asks us to consider if an object “sparks joy.” Morris, on the other hand, asks more systemic questions: Who are the workers behind the object I’m holding? Do the workers live a life of poverty and misery? Who benefits from their labor? Is this object a necessity or just a scheme to make money? And, most importantly, what would happen if the workers themselves had control over their production? Morris says,

I feel dazed at the thought of the immensity of work which is undergone for the making of useless things. It would be an instructive day’s work for any one of us who is strong enough to walk through two or three of the principal streets of London on a weekday, and take accurate note of everything in the shop windows which is embarrassing or superfluous to the daily life of a serious man. Nay, the most of these things no one, serious or unserious, wants at all ; only a foolish habit makes even the lightest-minded of us suppose that he wants them, and to many people even of those who buy them they are obvious encumbrances to real work, thought, and pleasure. But I beg you to think of the enormous mass of men who are occupied with this miserable trumpery, from the engineers who have had to make the machines for making them, down to the hapless clerks who sit daylong year after year in the horrible dens wherein the wholesale exchange of them is transacted, and the shopmen who, not daring to call their souls their own, retail them amidst numberless insults which they must not resent, to the idle public which doesn’t want them, but buys them to be bored by them and sick to death of them.

Morris goes on to summarize his thoughts in a simple all-caps maxim, “THE WORK MUST BE WORTH DOING.” I like this a lot better than whether an object “sparks joy” or not. The slogan reminds me of David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs which shows in sometimes funny, sometimes gut wrenching detail how much of the work done in our time is meaningless, unnecessary and destructive of the planet and the mental health of so many people.

A common misunderstanding of Morris message is that he thought that we should all go back to hand work. It’s clear from reading him that it isn’t a matter of machine vs. hand work but rather what those machines are currently being used for and who is in command of them. We might decide, in a better future, to use machines to reduce drudgery rather than just accumulate profit. Morris says,

And all that mastery over the powers of nature which the last hundred years or less have given us : what has it done for us under this system ? In the opinion of John Stuart Mill, it was doubtful if all the mechanical inventions of modern times have done any-

thing to lighten the toil of labour: be sure there is no doubt that they were not made for that end, but to make a profit. Those almost miraculous machines, which if orderly forethought had dealt with them might even now be speedily extinguishing all irksome and unintelligent labour, leaving us free to raise the standard of skill of hand and energy of mind in our workmen, and to produce afresh that loveliness and order which only the hand of man guided by his soul can produce ; what have they done for us now ? Those machines of which the civilised world is so proud, has it any right to be proud of the use they have been put to by commercial war and waste?

But there’s another crucial difference between Kondo and Morris. Morris does not believe that we can somehow vote with our wallets to solve the crisis of capitalism. It’s not a matter of individual action. Morris says that we need to join together with other people to make systemic change, to wrestle power away from the capitalist class,

And how can we of the middle classes, we the capitalists, and our hangers-on, help them? By renouncing our class, and on all occasions when antagonism rises up between the classes casting in our lot with the victims : with those who are condemned at the best to lack of education, refinement, leisure, pleasure, and renown ; and at the worst to a life lower than that of the most brutal of savages in order that the system of competitive Commerce may endure.

There is an active, intentionality to Morris’ question, “Is the work worth doing?” Contained within this pithy slogan is a challenge to the “free hand of the market,” the alleged autonomy of capitalism that claims that a system, not people, determines what work gets done. In the world that Morris imagines, the workers decide what work is worth doing and what to do with surplus profit. Collectively, we might put aside some of that surplus for, say, a possible pandemic or other emergency. We might give young parents more time with their newborns. We might give families more time to take care of elders. We might make sure that everyone has a home and healthcare. What we wouldn’t have is what Marx called a “bad infinity,” the drive to more and more profit accumulation that comes at the expense of the life of this planet.

It’s easy to slip into hopelessness and nihilism when reading Morris’ still incendiary words. He hoped for peaceful, revolutionary change in Britain and the U.S. that never came. In fact, all of the worst aspects of the 19th century: war, environmental catastrophe, the continued dis-empowerment of the working classes only accelerated. And we’re surrounded by more ugly, useless crap than Morris could have ever imagined even in his worst nightmare.

The main problem with nihilism is that it leads to inaction. It says that you don’t care about future generations and should just give up. As Assata Shakur says, “Our young people deserve a future, and I consider it the mandate of my ancestors to be a part of the struggle to ensure that they have one.”

You can read Morris’ speech, Art and Socialism in a book Architecture, industry & wealth; collected papers for free on Archive.org.

Great topic, I have always been a dumpster diver, recycler,

upcycler, repairer….admirer of well-made useful things.

I find myself constantly wondering when I look at the useless, cheaply made plastics that inundate all of the planet, how many meetings, how much energy, time and decisions did it take to bring that item into existence? What are the consequences of that item being made?

Morris was asking all those questions and I thank you for recommending his work.

Because socialist/socialism are such loaded words in the U.S., I think we need some poets/artists/thought-stylists to come up with a fresher label for contemporary work.

Yeah, it’s a loaded word especially for people my age and older as we grew up during the cold war. Some have suggested “post-capitalism” but it doesn’t have much of a ring to it. The younger folks I know are not as hung up on the “S” word.

This is a beautifully written and thoughtfully presented post. Thanks so much! William Morris is and always will be my hero.

Thank you!